Weinblatt, U. (2018) Mentalisieren und Spiegeln. In von Sydow, K., & Borst, U. (Eds.). Systemische Therapie in der Praxis. Beltz. (pp.291-301) Translated.

Mentalization and Mirroring

Uri Weinblatt

Background and General Characteristics

Escalating emotions and the inability to accurately perceive other family members' motives and intentions are common situations in family conflict. In mentalization-based treatments these events are understood to reflect an undermined capacity by one or more family members to mentalize – that is, to accurately make sense of their own and the other family members' subjective experience. When the ability to mentalize is jeopardized, the ability to interpret successfully the experience of the self and of others is reduced, leading to emotional reactivity and what we commonly view as ineffective communication patterns: blaming, accusation, interruptions, faulty mind reading and avoidance.

What is Mentalization

Mentalization is the process by which we conceive and understand mental states of ourselves and the mental states of others. While Mentalization is relatively a new concept, earlier terms such as self-awareness, introspection, reflectiveness, observing ego, metacognition, and theory of mind refer to similar processes. Mentalization is the ability to have perspective over the emotional experience of one's self and others', to "see ourselves from the outside and others from the inside" (Asen & Fonagy, 2012). When people are able to mentalize they can identify more clearly their thoughts and needs, and become less emotionally reactive. It is the process of being mindful of what is happening rather than being mindless. Because mental states are always changing, mentalization is never exact and demands a continual process of reflection and the flexibility to accommodate to new information. Mentalizing is a process that occurs constantly in our relationship with our self with others, yet the ability to mentalize effectively comes and goes and is depended on many factors including one's history, level of stress and relevant contextual factors. When mentalization capabilities are compromised, disruptions in self-regulation and in interpersonal relations are expected.

Mentalization in Therapy

In recent years, the mentalization perspective has emerged as a valuable bridge between psychoanalytic thinking and systemic discourse (Donovan, 2015). As an integrative concept which unifies processes within the self and in familial patterns, mentalization has become a useful tool for a wide range of practitioners for understanding family dynamics as well as a basis for pragmatic interventions. Mentalization theory is originally based on Bowlby's Attachment theory, viewing successful mentalizing capacity as an outcome of an attuned parenting to the infant's needs. As parents mirror the child's response adequately, his ability to make sense of his own mental states develops. However, the relationship between mentalizing and attachment seems to be more complicated and have a more bi-directional causality, meaning that it is also the capacity to mentalize that effects the quality of the attachment. This correlation between the mentalizing quality and the quality of the relationship is embedded and continues throughout life – the healthier our relationship the greater the chance for successful mentalizing and vice versa: the more effective the mentalizing is – the greater chance for a successful relationship.

Indication, Contraindication and Side Effects

Individually-oriented mentalization-based treatments were originally designed to treat Borderline Personality Disorder, a disorder in which the inability to mentalize effectively leads to stark difficulties in emotional regulation and interpersonal relationships (Bateman & Fonagy, 2006). Yet reduced capacity to mentalize shows up in other common disorders and in problematic relationships in general. As such, it was transferred to relational and systemic oriented treatment, in which mentalization skills and capacities are considered crucial in determining whether daily family conflicts will escalate and lead to adversarial interactions or will be contained and lead to successful problem solving and reconciliation. Moreover, it is the ability to mentalize which is the goal of the different interventions, and such ability is the main criterion of whether the intervention was successful or not. The most elaborated form of therapy integrating mentalization theory and systemic principles was developed by Eia Asen and Peter Fonagy. According to this therapeutic approach (Asen & Fonagy, 2012) difficulties in mentalizing have a persistent negative influence on family functioning. MBT-F aims to address these difficulties in mentalizing and enhance effective mentalizing (known also as mentalizing strengths). Many other therapeutic approaches also focus primarily on increasing family members' ability to mentalize but without using the term mentalization per se. What is common in these mentalization oriented treatments is the constant effort of the therapist to create a "platform" (Wile, 1993) – a non accusing and non anxious vantage point from which clients can monitor their changing thoughts and feelings instead of being swallowed up in them. Being on a platform enables family members to sympathize with themselves and with others for having states of mind which they have only limited control over. Being on a platform develops perspective and a compassionate attitude that helps in dealing with even chronic emotional problems which demand ongoing efforts to manage.

Mentalizing interventions are very useful in situations of impasse and even more specifically in situations where the therapist-client rapport has been damaged. Suppose for example a therapist says something that leads to an angry reaction from the client. In such situations, the therapist can check with the client "did I say right now something that upset you?" but can also ask a question that facilitates a stronger mentalization process for the client, for example – "how much of what I have just said seems critical or unfair to you and how much of it seems reasonable?"

While Mentalization interventions can enrich therapeutic processes and be highly effective in resolving relational problems, there are situations in family therapy in which the clients need specific instructions on how to move forward. This is often the case in working with parents of children or adolescents who are in a state of crisis and need immediate tools to deal with risk behavior. Such situations do not profit from increasing the reflective capacity of the parents. What parents need in such moments is direct action and a specific plan. Therefor it is wise in such situations to withhold the mentalizing work to a later stage in therapy, where parents have already some answers to practical questions like "what do we do if our son runs away?" or "what do we do if he doesn't want to wake up and go to school". This being said, integrating mentalizing work in even pragmatic parent training models can be very useful. For example, before suggesting a "tough" intervention to parents who have an adolescent who behaves aggressively, enhancing the parents' mentalizing can help them accept the intervention or think about in a more creative way. In such situations, a sentence like "I am going to propose an intervention that you can do with your son but I must tell you that I am not totally sure that I should suggest it to you because you might feel it's too tough and it might scare you away" allows the parents not only to react directly to the suggested intervention ("it's too tough! He'll run away! We can't do it") but to be in a position of evaluating their own initial response ("you are right this does sound pretty tough, but it's good that you suggested it, we just need to think how to work this out for us").

Practical Implementation

Mentalization interventions can be implemented from the first moments of therapy session. For example a client enters the therapeutic room and sits quietly without saying anything. A non mentalizing therapeutic solution to such situation is to help the client warm up by asking questions: "how was your week?", "How was the level of anxiety in the last days?" A mentalizing attitude on the other hand will treat such a situation with a question such as "I am wondering wha'ts happening for you right now, are you silent because, a) you had a great week and don't have anything to say, b) Something negative happened but you don't know whether you want to talk about it, or c) something else?" this "multiple answer question" facilitates within the client a reflective attitude towards their silence. Through comparing his or her experience to the different options raised by the therapist, the client can identify more clearly the cause of the silence and has an easier opportunity to verbalize it. As the example demonstrates, although the therapist confronts directly the issue occurring in the here in now, the confrontation is done in a soft and collaborative spirit. As a result, such interventions do not arouse usually resistance from clients.

Integrating Mentalization with Other Systemic Approaches

Leading mentalization scholars have emphasized repeatedly that mentalization is a therapeutic stance that can be adopted by therapists working primarily with other therapeutic approaches. Indeed, the spirit of collaboration and curiosity, as well as techniques fostering mentalization, are shared by many systemic approaches. For example, the mentalization strength of "perspective taking" is also cultivated through circular and reflexive questioning in different constructivist and collaborative approaches (selvini et al., 1980; Tomm, 1987), and the mentalization strength of "reflective contemplation" is closely related to the work of reflecting teams (Anderson, 1987). Peter Fonagy (2013) has observed that mentalization is a common component of all successful psychotherapies: "You, as a therapist have to be able to create in your mind some image of my mind and communicate that to me in such a way as to help reorganize my mental world … experiencing you making sense of my thoughts and feelings will help me organize myself". (p. 18). Perhaps the most common therapeutic practice to accomplish this goal is mirroring and reflection. Mirroring is considered one of the basic ways for regulating emotions. It is through mirroring that the child learns to understand what it means to have emotions and to regulate them. In psychotherapy, it is through mirroring and reflections that we communicate empathy and understanding – the most powerful tools that heal pain and suffering and it is through mirroring that we learn to know ourselves and to know others.

Mentalization, Systemic Mirroring and Shame Regulation

Mentalizing is assumed to emerge out of successful mirroring, which is achieved when two people together generate, communicate, and integrate meaningful elements of their respective experiences. This creates an experience of implicit relational knowing. This “knowing” results in an organized dyadic state which leads to mutual emotional regulation.

Shame is the emotion that has most to do with knowing the self and knowing others. Shame is a prevalent and painful emotion that arises in everyday life and can contribute to many problems that clients bring into therapy, including interpersonal difficulties and poor life functioning (Tangney & Dearing, 2002). Shame has much to do with mentalization because it tends to arise in conjunction with cognitive appraisals of the self. When we do not meet our standards, and begin judging, accusing and blaming ourselves we are actually experiencing shame. While shame can be triggered from observing the self, it can also be easily triggered when others evaluate us negatively, leading to an experience of feeling small, exposed and powerless.

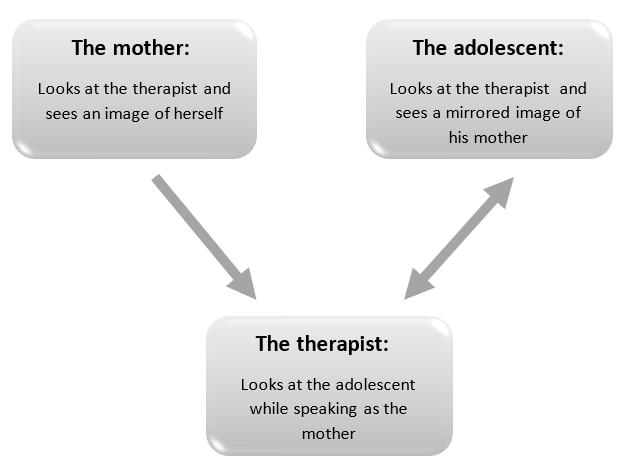

When family members become exposed to the mental processes of their self and others they become vulnerable to experience shame. This vulnerability should be handled carefully or it will lead family members to experience too much hurt and pain that can lead to negative therapeutic results and even the termination of therapy. A new approach of how shame can be managed and regulated in such situations is provided by the "Systemic Mirroring" approach (Weinblatt, 2016). The main intervention in this approach consists of a therapist meeting with two family members (parent-child, a couple or two siblings). As the conversation between the two-family members develops, shame is often triggered both by the content discussed (which exposes weaknesses and vulnerability) and by communication processes such as accusations, lack of recognition and ignoring that belittle, humiliate and hurt the participants. The therapist's goal is to regulate the shame in the conversation. This is done primarily through the act of speaking as if he or she was one of the participants. As the therapist "jumps into the shoes" of one family member, he/she forms eye contact with the other. Thus, a triangle develops in which one family member is watching and observing the therapist talk as if he or she were that person, and the other family member gets into direct contact with the therapist (or more accurately, the therapist becoming the other family member) (see Figure 1). For example, in a session between a mother and her adolescent son, things begin to heat up resulting in a non-mentalizing statement from the mother to the son: "You don't care about anything, you think only about yourself! You are so egocentric!" Without the therapist intervening, such a statement will lead to a non-mentalizing/shameful reaction by the son: "look who is talking! You are the worst mother ever!" The therapist needs to insert quickly a translation of the mother's initial statement to a mentalizing statement. Thus, before the adolescent can reply to the mother, the therapist asks permission to speak as if he was the mother: "you mother said something important and I want to see whether I understand you correctly, so I am going to speak as if I am you, is that ok?" Then he looks at the son and says "what I thought your mother just said was 'I know that what I am saying sounds harsh, accusatory and even unfair but I am saying this only because I am really hurt and afraid you don't care about me'". Such an improved statement can shift the listener (adolescent) from a defensive reaction to a more mentalizing position, which could lead to a response such as "yes, what you are saying hurts me and makes me angry at you. But it's not true that I don't care about you".

Figure 1: The Reflections in Systemic Mirroring Intervention

When this triangle is viewed through mentalization lens, we see a number of mentalizing promoting actions:

- By speaking for the mother, the therapist gives her a "voice", enabling her to communicate a wider set of feelings and beliefs. As the mother observes the therapist becoming her (but an improved mirror image of herself, with mentalizing capacity), her ability to mentalize grows both from the act of observing and from identifying with what the therapist says.

- By speaking for the mother, but in a more softened and mentalizing way, the therapist can facilitate positive mentalizing activity within the adolescent. Thus, the adolescent, instead of a hearing a non-mentalizing/shame provoking statement hears a mentalizing statement that promotes mentalizing activity within himself. This leads also to a cycle where connection is developed, which facilitates further mentalization.

- By speaking for the mother, the therapist protects his own ability to mentalize and remain empathic. By speaking for the mother, the therapist can neutralize his own negative judgments towards her ("I can't believe she said that to her son, that was really unnecessary and mean of her!") and replace them with a more productive mentalizing state of mind ("she was deeply hurt by what her son just said, I wished she could communicate it in a less destructive way, I'll help her to do that").

As the therapist continues to replace the family members' non-mentalizing statements with mentalizing statements, cycles of mentalizing develop. From an emotional regulation point a view, such cycles lead shame to become regulated for both family members, thus replacing adversity with collaboration, and isolation with intimacy. In helping family members to become truly known to themselves and to others, mentalization-based interventions help in lowering the mask of shame and promoting a living that is richer, less symptomatic and more authentic.

Case study:

Michael (14) arrived with his father to therapy because he has been staying at home and not going to school for four months. He had seen a psychiatrist a few weeks after stopping going to school and was diagnosed with social phobia and depression and began taking antidepressant medication which did not lead to any change. He was referred earlier to another therapist specializing in anxiety but because Michael did not say a word throughout two whole sessions the therapist acknowledged to the parents that he cannot help their son. The beginning of the session began as expected:

Therapist: So tell me what brings you here?

Father: Michael is refusing to go to school, we tried everything but he remains in his room, playing on his computer. He is also not willing to see his friends.

Therapist (to Michael): and what are your thoughts about what your father have just said?

Michael: (saying nothing, remaining silent).

Often silence, especially for adolescents and young men, reflects an inability to mentalize effectively and not a position of rebelliousness and resistance as many interpret it to be. The therapeutic challenge is to enhance the mentalizing capacity for a person who is not only disconnected from others but disconnected from his self. In the Systemic Mirroring approach we do this by speaking for the client. As the client observes the therapist imitating a mentalizing attitude for him – a process of identification begins. This can lead the client to regain their ability to mentalize.

Therapist: ok Michael let me speak as if I am you and you let me know if I am in the right direction ok? (then therapist looks towards the father). Ok father, if I would have been Michael my thoughts concerning your words would be "I have heard all this before. I don't know why I am not going to school, and I am also a little sick of talking about it". (then looks again at Michael) "does this sound like your experience?"

Michael: (Only slightly nods his head)

Therapist: And you father, what's your response to hearing this?

Father (angrily): What do you mean you don't know why you are not going?? And what do you want, not talk about it?!

Therapist: ok father you said some important things, and now I would like to jump into your shoes and speak as if I am you. (looking at Michael) what I heard your father say is "When You say I don’t know why I am not going to school I worry because it feels like we can't solve the problem. And just for the record, I am also sick from talking about this issue, it has been affecting all us in painful ways".

Therapist (to father): Is that how you feel?

Father: Yes, it's exactly like that.

As the therapist continued to speak for both the father and Michael the conversation deepened and Michael seemed more engaged. Fifteen minutes into the session he began speaking saying things like "yes, it's like that", or "no, you got it wrong". A session later he was producing his own sentences spontaneously. The focus of an mentalization oriented therapeutic process is to reignite the ability to mentalize. We thus focus on "solving the moment" – that is solving the problem of not being able to mentalize successfully rather than "solving the problem" – which means trying to find pragmatic solutions to the problem. In situations of school refusal, therapists often rush to find solutions and problem solve. Yet, often a more effective way to move forward is to help the adolescent reconnect first with himself and his emotions. This cannot be done without enhancing his mentalizing abilities. As the child's ability to reflect upon his experience (instead of dissociating from it) develops, his willingness and ability to find solutions grows naturally. As Michael regained his ability to "have a voice" his connection to both his own mental life and his family grew and his shame level reduced. In the following sessions his willingness to participate in life steadily returned. Two months after starting therapy Michael announced to his mother that he wants to celebrate his birthday (which he cancelled a half year earlier when he disconnected from everybody). A few weeks after reconnecting with his friends, Michael returned to School.

Good Experiences, Typical Difficulties and Mistakes

Wile (1993) has said "intimacy is always one sentence away". Indeed, when a therapist helps family members voice what they really wanted to get through and were not able to – a powerful emotional reaction occurs which can lead to greater connection and motivation to change. Wile is accurate that moments of intimacy are waiting just around the corner – waiting for the right words to reveal them. Yet when working with families in which emotions are highly unregulated moments of intimacy and effective mentalization can be be replaced without warning with states of allientation and escalation. Anticipating this "roller coaster" is the best way for therapists to maintan their own effective mentalzing, otherwise they can become judgmental and lose their ability to effectively lead the family. For example in a couple therapy session a husband, finally, says to his wife "I care about you and love you". Yet the wife, surprisingly does not seem happy and even seems angry. In such moments therapists can lose their own ability to mentalize, thinking to themselves "she got what she wanted and she is still unhappy – maybe her husband is right to say that she is never happy with what he does!" Anticipating such moments can help therapists maintain their ability to think in helpful ways. Thus instead of thinking "she is ruining the therapeutic process" the therapist can insert quickly, before the husband gets hurt and offened, a sentence such as "your husband said warm words toward you yet you don't seem like you are jumping in joy. I want to see if I understand you correctly. Is your reaction a result of thinking 'It is really nice what he is saying but I don't understand why it took him so long. If he can say these things to me right now why didn't he say them before we came to therapy? So much suffering could have been avoided'". By adding such a statement, the therapist does not only regulate the communication between the partners and protects their ability to mentalize, but also protects his or her own capacity for mentalizing.

The clearest sign that therapists' capacity to mentalize is decreasing is when their ability to have empathy for the client deteriorates. This "loss of empathy" can serve as a clue for therapists who want to know when their mentalizing abilities are reduced. This loss is also often associated with therapists experiencing shame. The sources of this shame include:

- The therapist feeling they are failing to help the client.

- The therapist being blamed or accused by the client.

- The client not accepting the therapist's authority.

- The therapist making a mistake, saying something that leads to client being hurt.

Such shame evoking triggers can lead therapists to a non-mentalizing position which leads often to either alienated or adversarial dynamics with the clients. Being aware of their own empathy levels towards clients, can help therapists become aware of their own shame and ability or inability to mentalize effectively. Knowing that such states are common and occur often in sessions helps therapists not be become shamed for experiencing shame.

Critical Review

Mentalization in general has been empirically linked to important findings in child development and psychopathology (Allen & Fonagy, 2006) and initial evaluations of mentalization oriented treatments have shown promising results (Keaveny et. al., 2012). In a more recent randomized controlled study Mentalization Based Treatment was found to be helpful in the reduction of anger, hostility, paranoia, and frequency of self-harm and suicide attempts for patients suffering from comorbid Borderline and Antisocial Personality disorders (Bateman et al., 2016). Yet since mentalizing takes part in many diverse types of treatments in general and increasingly in systemic oriented treatments, it is difficult to isolate and evaluate the mentalizing interventions compared to other interventions. Future research will need address this challenge.

FAQ

How do I know that the client is effectively mentalizing?

When clients are effectively mentalizing collaborative interpersonal cycles are generated. These cycles are characterized by curiosity and respect and lead further to greater connection. When people are mentalizing effectively they use words which are softer and leave room for exploration, for example – "sometimes I wonder if I am making all this up". Effective mentalizing shows up also in the way clients relate to the therapist. Thus, instead of ignoring the therapeutic relationship or being critical towards the therapist (as happens in no effective mentalizing states) in an effective mentalizing state the client can relate in a honest way to the therapist "I happy to be here but also a little anxious because I am not sure what you think about what I told you last session".

How does it feel to mentalize?

While mentalizing has a clear cognitive component it is also experienced on an emotional level. The clearest experiential signs include empathy and compassion towards the self and towards others. Regaining the capacity to mentalize entails in general the ability to feel emotions which were blocked and excluded from awareness. Thus clients who could not feel sadness, shame or even positive emotions such as joy, experience through effective mentalization a the legitimacy to feel them.

Why does mirroring enhance mentalization?

Mentalization occurs as a result of "the meeting of minds". When another person mirrors our experience, our experience transcends it's confined status of being only in our minds. It becomes an object that can be observed, played with and changed. This building of perspective results in greater capacity to mentalize. Furthermore, mirroring is the most basic action which reduces shame. It is through mirroring that we fulfill the basic need of being seen by others. When this occurs we feel validated, our shame level reduces and our capacity to look at ourselves (and others) in non-critical ways is enhanced.

What do I do as a therapist if I lost my ability to mentalize?

Everybody's ability (including therapists) to effectively mentalize comes and goes. In relationships, the capacity to mentalize often changes moment by moment without the participants being aware of these changes. Therapists can and should, anticipate these fluctuations, expect them, not be ashamed of them and have a plan how to snap out of these states. The clearest sign of being in a non-mentalizing state is becoming increasingly judgmental towards the clients or in short losing the ability to empathize. One way to regain this ability is to speak for the client or "become" the client. This awakens mentalizing capabilities within the therapist, which usually leads to an effective mentalizing on the client's part ("yes I know that what I just said sounded really mean and was unhelpful") which further arouses a natural empathic response from the therapist ("don't worry about it, you have the right to be angry here").

7) Further Reading

Weinblatt, U. (2018). Shame Regulation Therapy for Families. Springer International Publishing:.

8) References

Allen, J. G. & Fonagy, P. (2006). Handbook of Mentalization-Based Treatment. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons

Andersen, T. (1987). The reflecting team: dialogue and meta-dialogue in clinical work. Family Process, 26: 415–428.

Asen, E. and Fonagy, P. (2012). Mentalization-based therapeutic interventions for families. Journal of Family Therapy, 34: 347–370.

Bateman, A. W., & Fonagy, P. (2006). Mentalization Based Treatment for Borderline Personality Disorder: A Practical Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bateman, A., O'Connell, j., Lorenzini, N., Gardner, T, & Fonagy, P. (2016). A randomised controlled trial of mentalization-based treatment versus structured clinical management for patients with comorbid borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1). doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1000-9

Donovan, M. (2015). Systemic psychotherapy for ‘harder to reach’ families; mentalization-based therapeutic interventions for families and the politics of empiricism. Journal of Family Therapy, 37: 143–166.

Fonagy, P. (2013). Interview with Peter Fonagy by Martin Pollecoff. The Psychotherapist, 53: 16–18.

Keaveny, E., Midgley, N., Asen, E., Bevington, D., Fearon, P., Fonagy, P., Jennings-Hobbs, R. and Wood, S. (2012) Minding the family mind: the development and initial evaluation of mentalization-based treatment for families. In: Midgley, N. and Vrouva, I. (eds.) Minding the Child. Routledge, Hove and New York

Selvini, M. P., Boscolo, L., Ceccin, G. and Prato, G. (1980). Hypothesizing –circularity – neutrality; three guidelines for the conductor of the session. Family Process, 19: 3–12

Tangney, J. P., & Dearing, R. (2002). Shame and Guilt. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Tomm, K. (1987). Interventive interviewing: Part 11. Reflexive questioning as a means to enable self-healing. Family Process, 26: 167–183

Weinblatt, U. (2016). Die Nähe ist ganz nah! Scham und Verletzungen in Beziehungen überwinden. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht

Wile, D. B. (1993). After the fight: Using your disagreements to build a stronger Relationship. New-York, NY: Guilford Press.