Weinblatt, U. (2013) Elterkonlikte Loesen: Einbeziehung von Paar-therapie-Inreventionen in das Elterncoaching. Systhema (1) (pp. 6-19) (Translated)

Resolving Parent Conflict: Blending Couples Therapy Interventions into Parent Coaching

Uri Weinblatt

Abstract

One of the challenges of parent coaching is how to deal constructively with parent fights and conflicts during sessions. The difficulty is a result of the shift the parents are doing, from focusing on the relationship with the child to focusing on their relationship as parents. A model for regulating and resolving these conflicts is presented. According to this model, parent fights are a sign that the parents’ relationship has shifted from a collaborative parent state to an adversarial parent state. I describe how therapists should shift their own position to match these different parent states and the ways of using these shifts as opportunities for improving the parents’ ability to communicate and empower each other.

The field of family therapy has been going through a process of specialization in the past forty years that led to the emergence of two major domains of expertise – couples therapy and parent coaching. In this process, therapies designed specifically for resolving the main concerns of each subsystem were developed, resulting in impressive empirical outcomes for both couples therapy and parent coaching. At the same time, the split between the parenting subsystem and the couple subsystem has created new therapeutic challenges, one being the question of how to respond to marital fights while doing parent training[1]. Many therapists fear this situation, feeling that parental conflict might lead to loss of focus, confusion and a disruption to the structure of the parent coaching process. To prevent such an outcome, therapists often respond with a number of improvised solutions: 1) have the parents undergo couples therapy before parent coaching; 2) Have the parents go through parent coaching and couples therapy at the same time with different therapists; 3) Have the parents “control themselves” and not allow for couple issues to enter parent coaching sessions; 4) refer them to family therapy which includes all family members. While each option has some advantages, they are all based on the idea that parent coaching and couples therapy are practices that do not fit together. The research and theoretical literature also support this assumption. An approach for providing parent coaching and couples therapy at the same time has yet to be developed in a systematic way.[2] Without such a guiding model many therapists who try to resolve parent fights during parent training sessions have to rely mostly on improvisations and can easily lose direction. The goal of this paper is to provide a preliminary model for handling, regulating and resolving parent (couple) conflict during parent coaching. The model is based on an integration of two approaches that inform my work with families: on the one hand, the Non Violent Resistance (NVR) parent coaching model (Omer & Schlippe, 2002, 2004), and on the other hand, Collaborative Couple Therapy (Wile, 1993, 2011). My goal in this integrative model is to enable therapists to switch from focusing on the parenting behaviors and skills (what we mainly do in parent coaching) to focusing on the parents’ relationship (what we sometimes do in couples therapy) while maintaining the structure and integrity of this process. The basic assumption of the model is that parents switch in and out of two basic interactional states – “the collaborative parent state” which yields itself well for parent coaching interventions, and “the adversarial parent state” that demands a couple oriented position in order to be regulated.[3] For therapists to work effectively with parents they need to be able to 1) identify when the shift from the collaborative to the adversarial parenting state occurred and 2) to change their therapeutic position to match this shift. This paper will describe this process. I begin by describing theoretical aspects of the parents’ relationship. Then I describe the main differences in the therapeutic position regarding collaborative and adversarial parent states. From there I present ways for regulating adversarial states, and finally, I show how parents can do this type of regulation on their own – transforming moments which could have led them to fight each other to moments of support, parental empowerment and increased intimacy.

The Collaborative and Adversarial states of the Parents’ Relationship

Parents have a relationship with each other around their parenting. This relationship, called Coparenting (Wiseman & Cohen, 1985), is considered separate from the romantic and sexual aspects of the marriage and has been defined as the extent to which partners support or undermine each other in dealing with their children (Feinberg, 2003). While there is some overlap between the couple relationship and the coparenting relationship, not all distressed marital relationships become distressed coparenting relationships, and not all parents with negative coparenting dynamics are unhappy with their relationship as a couple (Cowan & McHale, 1996).

Different researchers have made efforts to identify the different dimensions that compose the coparenting construct (Teubert & Pinquart, 2009). For example, Konold and Abidin (2001) who composed the Parenting Alliance Inventory (PAI) argue that the coparenting alliance is composed of two major variables – communication/teamwork and respect. Communication refers to the amount of agreement concerning discipline goals for the child. It includes questions such as “Talking to my child’s other parent about our child is something I look forward to”. Respect refers to the trust in the other parent’s commitment and judgment for the care of the child. It includes questions like “my child’s other parent tells me I am a good parent”.

For some couples, coparenting is a domain where their ability to coordinate the challenges of raising children becomes a major strength in their relationship. For others it becomes a battle ground, where differences and self interest lead to constant competition and conflict (Belsky et al., 1996). Coparenting has been hypothesized to be the mediating variable between marital conflict and child’s problem behaviors (Gable et al., 1992). It is where marital conflict transforms into ineffective parenting and where the child’s problem behaviors initially affect the relationship of the parents (Feinberg, 2003).

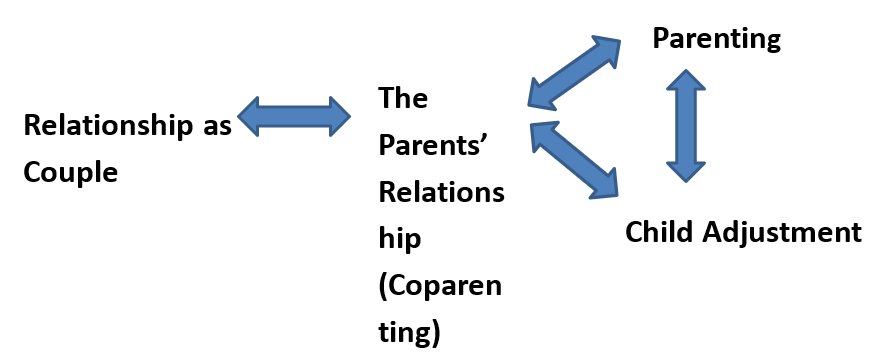

Figure 1: The centrality of the parents’ relationship in family dynamics

The parenting alliance is sensitive and can easily be impacted, whether by the couple relationship, the quality of parenting, or by the child’s behaviors (see figure 1). Since it is affected by different family dynamics, the parents’ relationship tends to shift from collaborative states in which the parents are supporting, encouraging and respecting the efforts of one another to adversarial states in which parents blame, criticize and feel disrespected by each other.

According to Wile (2011), who wrote extensively on adversarial dynamics in couple therapy, the two main causes leading to an adversarial dynamic are the loss of voice and the loss of connection. Losing voice means losing the ability to communicate the feelings which are most alive in a present moment. The loss of voice will often lead to a loss of connection. Without the ability to confide true feelings partners become less intimate and resort to communications that lead to anger, hostility and distancing. In the therapy room, the most typical signs that parents have shifted into an adversarial state include:

- Parents blaming each other for the child’s problems – “You are too tough! You are too soft”.

- Parents disagreeing on what is the problematic behavior – “I think it is a problem! No, I think that is normal!”

- Parents not listening to each other and willing to hear only the therapist.

- Parents attacking each other for being too involved or not involved enough.

I also know that the parents are in an adversarial dynamic indirectly – through the parents’ relationship with me[1] –

- One or both parents blame me for the child’s behavior.

- One or both parents show resistance to interventions.

- I am blaming one or both parents.

On the other hand, the collaborative parent state in manifested by the following signs:

- Parents can tolerate their differences and sometimes can even see them as strengths. They use humor to explain the differences in their style of parenting.

- Parents appreciate what the other parent is doing.

- Parents do not blame each other for the child’s problem.

- Parents admit to their role in the fights with the child and want to do something different.

- Parents can agree with some of the other parent’s criticism of their parenting.

Just as the adversarial state tends to affect the therapist so does the collaborative state. For example, when parents are in a collaborative state I notice that:

- I like the parents.

- I view the child’s behavior mainly as a result of his own vulnerabilities and difficulties.

- The parents welcome my interventions and are interested in them.

How Therapists Should Respond To Different Parental States

When therapists witness the shift from a collaborative parent state to an adversarial one they should respond by shifting their own position, otherwise they can easily find themselves being caught in the adversarial dynamics with one or both parents. What does it mean to be caught in adversarial dynamics with a parent? It means starting to view the parent (or parents) in a negative way, blaming them for all the child’s problems, seeing them as egocentric, childish, impossible and so forth. The two most common ways for therapists to enter into such dynamics with parents are:

- Being unable to stop the parents from fighting with each other.

- The parents resisting and not accepting the therapist’s interventions.

How do we prevent ourselves from being caught in such adversarial interactions? By adjusting and shifting our own positions – from the problem solving position that characterizes parent coaching, to the communication position that we often view as characterizing couples therapy. Whereas the problem solving position is highly effective when parents are in a collaborative state, the communication position is effective in reducing adversarial interactions.

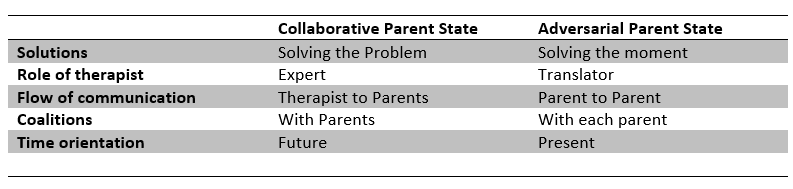

This change in the therapeutic attitude is manifested in a number of important dimensions (see Table 1). These include:

- Solutions – When parents are in a collaborative parent state solutions are a result of “solving the problem”. Thus therapists provide for parents new innovative ways of approaching and relating to their child. The more the parents are in a collaborative state with each other the more they are likely to use and try out the interventions offered by the therapist. However, when parents are in an adversarial state they can be offered the most creative parental interventions and still reject them. In adversarial parent states solutions are a result of a different therapeutic strategy which focuses on “solving the moment” (Wile, 1993, 2011). In solving the moment the therapist tries to give words to unexpressed wishes, fears or feelings that the parents cannot communicate to each other. In doing so the therapist is enabling a collaborative communication cycle to replace the more adversarial or alienating cycle that the parents are caught in.

- Role of the therapist – When parents are in a collaborative state the therapist‘s knowledge and expertise is welcomed and integrated with the parents’ understanding. In adversarial states the role of the therapist as a translator of each parents’ experience is a more helpful position. In these situations what the parents need more than anything else is empathy and understanding of their subjective experience. Interestingly, when parents are in an adversarial state they often want and even put pressure on the therapist to play the role of the expert and to decide “who is right and who is wrong”. Accepting such role when parents are in an adversarial state often gets the therapist in trouble.

- Flow of communication – in collaborative states information is effectively and constructively exchanged back and forth between the therapist and the parents. In adversarial states the flow of communication takes a different route and becomes focused on belligerent exchanges between the parents. In order to stop the parents from fighting, therapists often try to replace this communication flow with the one that resembles the collaborative state, namely, talking to the parents and having the parents respond back. This strategy usually gives temporary relief from the fight, but it does not provide a solution to what evoked the adversarial dynamic in the first place.[2] In such situations I prefer to remain in the parent to parent communication flow and to translate each parent’s position. By doing so I allow the needs, wishes and fears of each parent to be heard and ultimately to be regulated.

- Coalitions – Collaborative states according to Wile (1993) feel like “being on a platform”, which means that the therapist and parents are able to view the problem from a united higher ground. At these moments, the ability to relate to both parents at the same time is both possible and welcomed by the parents. In contrast, in adversarial states such relating is difficult. Therefore, a more helpful strategy is to shift constantly between developing a coalition with one parent to developing one with the other.

- Time orientation – When parents are in a collaborative state the effective therapeutic position revolves around planning for the future – how and in what way will the parents react when their child acts out. In adversarial states the therapist should focus more on what is happening in the present, namely the conflict between the parents. In doing so the parents are receiving the tools that will enable them to deal with their future conflicts concerning their parental differences.

Table 1: The therapist’s positioning in collaborative and adversarial parent states

Adjusting our therapeutic position to match the different parent states is very useful and at the same time raises the question of how can such shifts occur without confusing or evoking anxiety in the parents. My experience shows that shifting unexpectedly to meet the adversarial parent state (which means that the therapist is reacting in similar ways to a couples therapist) often leads parents to protest and say “we didn’t come to couples therapy!”[1] However, such responses can be easily prevented if the therapist prepares the parents for such shifts. Therefore, in the first session I ask permission from the parents to talk about their relationship as parents. I tell them explicitly that I have no intention of doing couples therapy with them but that my goal instead is to turn them into “the best team you can be”. Then I ask them whether they want me to talk about and improve their team work as parents. Almost all parents respond positively.

Parental conflicts as opportunities for increased parental intimacy

During session parents can switch from talking about the conflicts with their child to having a conflict within their own relationship. For classical family therapists this is a welcomed transition since the basic premise is that the main problem lies in the couple subsystem and that the child’s symptoms are mostly a symptom of these problems.[2] For other therapists, escalating parental fights are sign of significant marital issues which endanger the parent coaching process and demand a change in the format of therapy – from parent coaching to couples therapy. In my approach, I view these fights as part of the development of the parental alliance. I understand the intense reactions as desperate efforts to improve the parental relationship and the parents’ relationship to the child. The meanings I ascribe to these moments of conflict are:

Wanting recognition and respect. The often heard parental complaint “With me he never behaves in that way!” can easily be seen as a way of one parent to berate and criticize the other. I, however, prefer to view it as an ineffective effort to gain respect by the other parent. Therefore in such situations I intervene and say “I think what your partner was trying to say to you is ‘I don’t mean to criticize you but I wish you could see my success with our child and appreciate it’”.

A way of “making a point”. Parents use extreme statements in order to try and communicate more effectively an idea that is important for them. For example, if a father says to mother “You don’t know how to set boundaries! You let the children do whatever they want!”, I enter into the conversation and say to the mother “I think what your husband is trying to tell you is ‘I don’t want to be angry with you and I know that you care about our children but I am really worried that if our child will not experience more boundaries his behavior will become worse’”.

Wanting a different type of team work. Most parents who arrive to parent coaching are not working well as a team but have a hard time expressing it. Therefore, instead of saying “we are having a hard time cooperating together with our kids” they say “you always do the opposite of what I do!” or “why do you always have to give-in after I punish our child?” I turn these complaints into positive offers to try a different constellation of team work. For example, my response to “you always do the opposite of what I do!” would be – “o.k. what I hear your partner is trying to tell you is ‘ I know we have different styles in raising our children but I wish we could find a way to work better as a team and not have all this conflict between us’”.

Wanting to be able to talk more about the children. Other common complaints include “you are too tough!” or “you are too soft!” These complaints can lead a parent coach to search for parental interventions which combine both soft and hard aspects.[3] This approach can be very successful when the parental conflict is not too intense. I also like to use such complaints as opportunities to improve the parents’ ability to talk about their differences in parenting in a way that will make them closer to each other and more intimate rather than enemies and rivals. Therefore I respond to the too tough or too soft complaints with a statement such as “what I hear you partner is trying to say is ‘I know we have different styles but I wish that you listen to my ideas about parenting without thinking that I just want to criticize you’”.

Parents shifting out of adversarial states by themselves and in the process becoming more present

Positive recognition, communication and teamwork turn each parent into the best parent she or he can be. Yet methods for how parents use their relationship to empower each other have not been the focus of the parental coaching literature. I believe the reason for that lies in that such methods feel more like couples therapy interventions and are not focused directly on parenting skills or on child management techniques. This is unfortunate because each parent is in the best position to affect and improve the other parent’s sense of being present. However, when one parent is having a fight with the child the other parent can easily find themselves in a difficult dilemma – if they enter into the fight they might lead the other parent to feel that they are intruding, criticizing or not trusting their judgment about how to handle the fight. If they do not get involved, they might leave the other parent feeling angry or alone. I like to prepare parents for such moments. My experience has shown me that the moment in which one parent relates to the parent who just had a fight with the child, is a moment with enormous potential for increasing the parents’ experience of being present.

According to Omer and Schlippe (2002) three types of experiences lead parents to feel themselves as fully present:

- Moral/personal Presence –the experience of having values. When parents are morally present they are not confused and are saying to themselves “What I am doing is right and fair”.

- Behvioral Presence – The experience of having influence. When parents are behaviorally present they are not helpless and are saying to themselves “what I am doing works”.

- Systemic Presence – The experience of being supported. When parents are systemically present they are not isolated and are saying to themselves “I am not alone”.

In working with parents my goal is to facilitate a relationship between parents in which they can talk about their parenting in a way that strengthens their presence as parents and provides for intimate moments as a couple. I do that by helping the couple learn how to shift, in real time, from an adversarial mode of interaction into a collaborative one. In the next sections I show how different parental interactions can lead exactly to that. In each short excerpt I will show how the parental dialogue, which could have turned into a conflict or fight, turns instead into a collaborative interaction which helps the parent who was in a conflictual situation with the child to feel more present.

Strengthening the Moral Presence. In the first example, mother approaches father after he had a loud fight with the son. Both screamed, yelled and said hurtful words to each other.

Father -I feel like killing him!

Mother – Well, he sure knows how to press all the buttons.

Father –Yes, but I lost control and said things I should not have said!

Mother -Maybe, but you are still a good dad.

Initially, father is angry at the child. If mother had had a bad day she would have probably responded with statements such as “why do you always have to fight with him!” or “why can’t you control yourself? You are the adult!” But today mother is at her best and instead of blaming the father she responds first by legitimizing his anger. This creates a shift within father and helps him see that he is really angry at himself for acting in ways which do not match his values. As a result he feels shame and guilt. Mother shows understanding for his loss of control and reminds him that he is a good father.

Father -A good dad doesn’t call his son a stupid idiot!

This statement could shift the parents’ interaction into an adversarial one. The mother has already shown plenty of patience and could have had enough of the father’s complaints. She could have said something like “you are right, so don’t say such a thing again!” But mother is still in a collaborative state and instead tells father:

Mother- He said some awful things himself and provoked you, at the same time I know that you hate losing control like that, it’s not your style.

Father -You are right I hate being like that, it is not me.

Mother -And you care about him and are worried about him.

Father – I should let him know that without losing control and exploding.

Mother – with our son it is really hard being a Buddha. I lose control with him, you lose control and he definitely loses control. If you feel you need to apologize for your actions we can do that.

Father -Yes that’s what I will do.

Mother communicates to father that in her eyes he is still a good father. By doing so she is regulating the father’s shame and guilt. This leads to a pragmatic course of action, which helps father behave again in ways which he views as worthy and fair. Finding a way to act in accord with his values repairs the father’s moral presence. If mother had suggested to father to apologize without the whole regulation process he would probably have dismissed it and become angry at her.

Strengthening the Behavioral Presence. Mother approaches father after he had a fight with son concerning when to come back home after a party on Friday night

Mother -Thanks for taking care of that.

Father – But he didn’t listen to me at all and I don’t know why I always have to take care of it!

Although mother came with good intentions father is still angry and emotionally aroused from the fight with the child. He responds to mother’s positive statement by attacking her. This can easily lead to an adversarial interaction between the parents. However mother continues in a collaborative tone –

Mother – He listened to you more than he would have listened to me. If I would have been there things would have gotten worse.

Mother is doing something remarkable here. She shows father that he has influence over the child. She lets father know that she does not see his efforts as futile and meanginless but as positive and constructive.

Father – I guess you are right.

Mother – With all his arguing you still have some impact on him, I wish I had that.

Father – You are right he does listen to me sometimes.

In two sentences mother helps father regain his sense of behavioral presence. She focuses on his success and not on his failures. This helps father experience his own sense of influence and power.

Strengthening the Systemic Presence. Father approaches mother after she helped daughter with homework:

Father -Thanks for helping Maya with her homework.

Mother -Well someone has to do it!

Although father is trying to communicate recognition mother is experiencing his statement as meaning that helping the daughter with her homework will always be her job. She responds by attacking. This could easily lead to an adversarial dynamic (father responding with “You are not right I do a lot of homework with Maya!”) Instead father continues with a collaborative tone:

Father – I know, and I wanted to let you know that I notice what you do and I appreciate it.

Mother – You do?

Mother is not used to father communicating in such a way and is reacting with disbelief. However, she has already softened up.

Father – I probably should tell you this more often and not let you feel you are responsible for this and I am not.

Mother – It is not such a big deal but, I appreciate you saying this.

Only a few minutes ago mother felt frustrated and alone. Father’s words let her feel that she is valued by him, seen by him and cared by him. His recognition and support suddenly helps her feel that helping Maya is “not such a big deal”.

Can parents speak this way to each other? only if they are in a collaborative state. If they force themselves to speak this way when they are in an adversarial state it will come out false, insincere and be ineffective. Adversarial states are easy to fall into. In my work with parents I help them shift from adversarial states that are manifested in attacking, blaming and criticizing to collaborative ones. Doing this over time builds within parents the capacities to understand the deeper meanings of their conflict and ultimately to disarm their fights and become parents that can use their relationship as a positive emotional regulating force in the family.

References

Belsky, J., Putnam, S., & Crnic, K. (1996). Coparenting, Parenting, and Early Emotional Development. In J. P. McHale and P. A. Cowan (Eds.), Understanding How Family-Level Dynamics Affect Children's Development: Studies of Two-Parent Families. New Directions for Child Development, No. 74 (pp 45-55). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Cowan, P. A., & McHale, J. P. (1996). Coparenting in a Family Context: Emerging Achievements, Current Dilemmas, and Future Directions. In J. P. McHale and P. A. Cowan (Eds.), Understanding How Family-Level Dynamics Affect Children's Development: Studies of Two-Parent Families. New Directions for Child Development, No. 74 (pp. 93-106). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Feinberg, M. E. (2003). The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: A framework for research and intervention. Parenting: Science and Practice, 3, 95-131.

Gable, S., Belsky, J., & Crnic, K. (1992). Marriage, parenting, and child development: Progress and prospects. Journal of Family Psychology, 5, 276‐294.

Henggeler, S. W., Schoenwald, S. K., Borduin, C. M., Rowland, M. D., & Cunningham, P. B. (1998). Multisystemic treatment of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford.

Konold, T.R. & Abidin, R.R. (2001). Parenting Alliance: A Multifactor Perspective. Assessment, 8, 47-65.

Omer, H. & Schlippe A. v. (2002). Autorität ohne Gewalt : Coaching für Eltern von Kindern mit Verhaltensproblemen. 'Elterliche Präsenz' als systemisches Konzept. Goettingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Omer, H. & Schlippe A. v. (2004). Autorität durch Beziehung. Die Praxis des gewaltlosen Widerstands in der Erziehung. Goettingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Sanders, M.R., Turner, K.M.T., & Markie-Dadds, C. (1998). Practitioner's manual for Enhanced Triple P. Brisbane, QLD, Australia: Families International Publishing.

Teubert, D. & Pinquart, M. (2009). Coparenting: Das elterliche Zusammenspiel in der Kindererziehung. Psychologie in Erziehung und Unterricht, 56, 161-171.

Weinblatt, U. & Omer, H. (2008). Non-violent resistance: A treatment for parents of children with acute behavior parents. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 34,75-92.

Wile, D.B. (1993). After the Fight: Using your Disagreements to Build a Stronger Relationship. NewYork: The Guilford Press.

Wile, D. B. (2011) Collaborative couple therapy. In Carson, D.K. & Casado-Kehoe, M. (Eds.) Case studies in couples therapy: Theory-based approaches. New York: Routledge. pp. 303-316.

Weissman, S. & Cohen, R.S. (1985). The parenting alliance and adolescence. Adolescent Psychiatry,12, 24–45